The Shakespeare Authorship Question: Unravelling the Mystery

Who wrote the plays, and why?

In the vast realm of literature, few names resonate as profoundly as William Shakespeare. His plays and sonnets have captivated audiences for centuries, leaving an indelible mark on the world of poetry, prose and theatre.

Yet, despite his enduring legacy, a mysterious shadow looms over the Bard himself. For centuries, scholars, enthusiasts, and sceptics have debated the true identity of the man behind the works attributed to William Shakespeare.

Did he really write the plays and sonnets? It is a riddle that has sparked intrigue, speculation, and fuelled a fervent quest for the truth.

This quest is known as The Shakespeare Authorship Question.

There are many anomalies which have contributed to uncertainty over the authorship. Perhaps one of the most shocking is - and here I quote from the august institution, The Smithsonian - "There are no original manuscripts, Not so much as a couplet in Shakespeare's own hand has been proven to exist. In fact there's no hard evidence that Will Shakespeare of Stratford upon Avon, revered as the greatest author in the English language, could even write a complete sentence."

We know Shakespeare never mentioned the plays in any document, or his will. Nor did his widow, his daughters, their husbands or his grand-daughter ever claim he was the author of the plays.

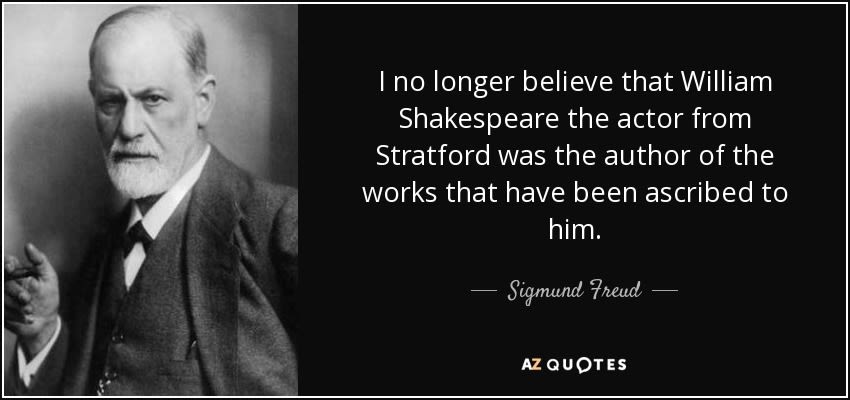

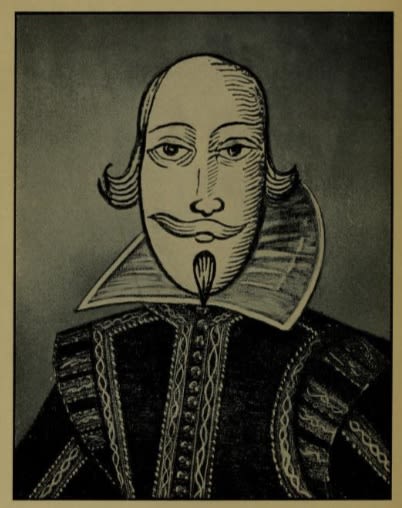

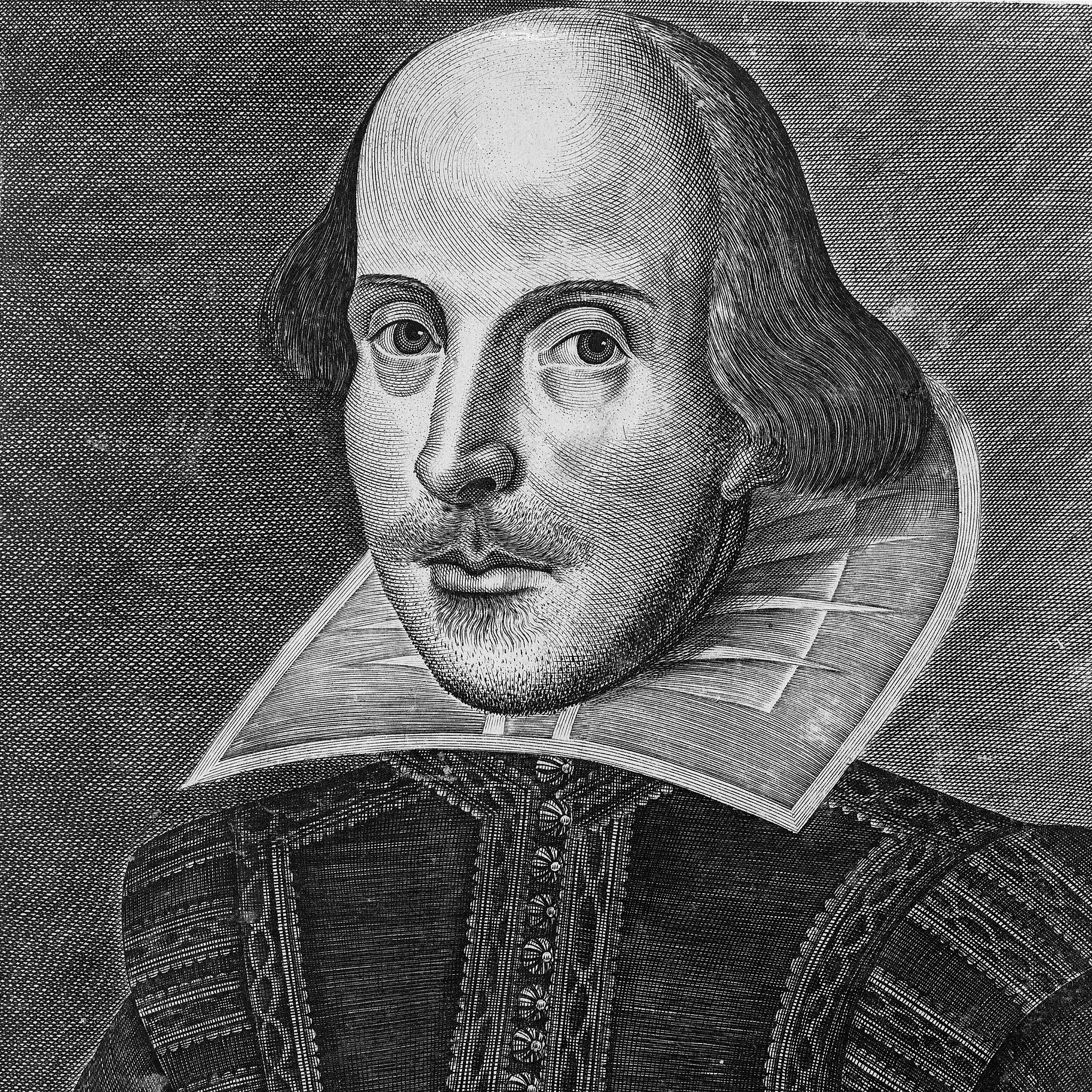

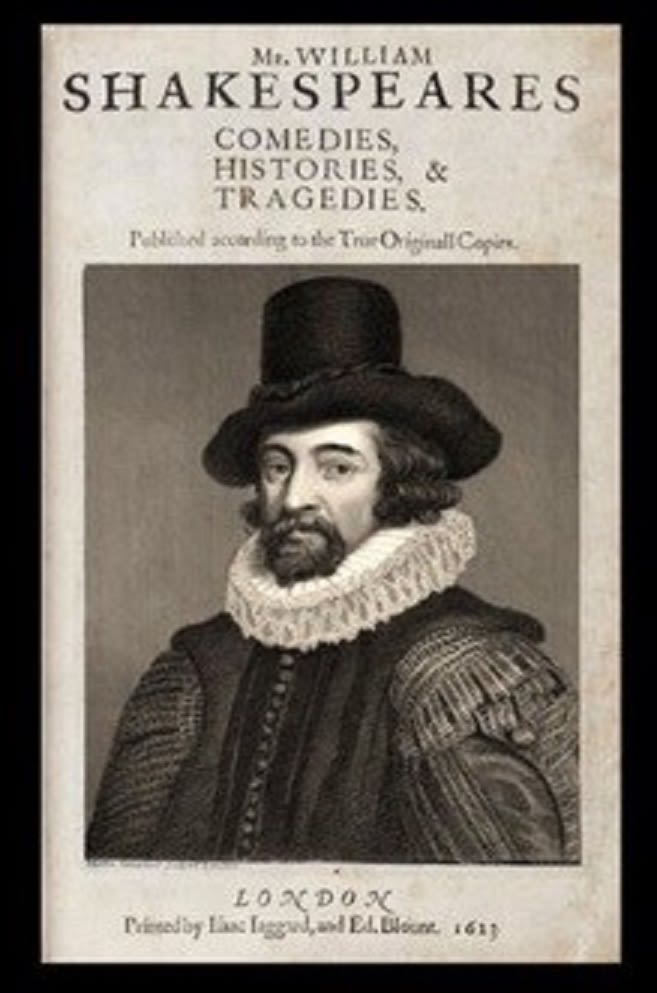

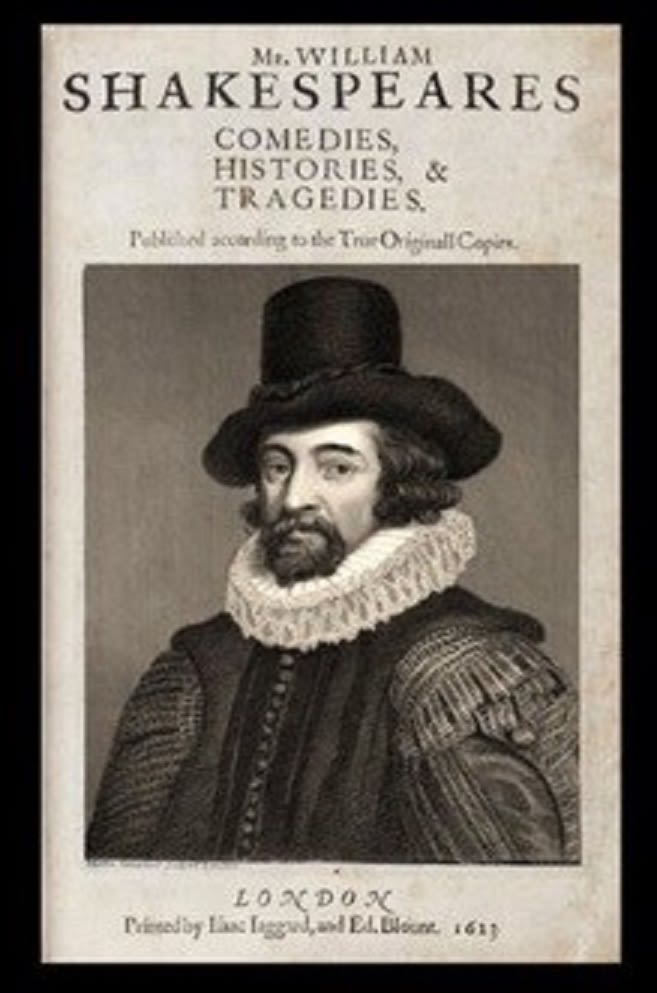

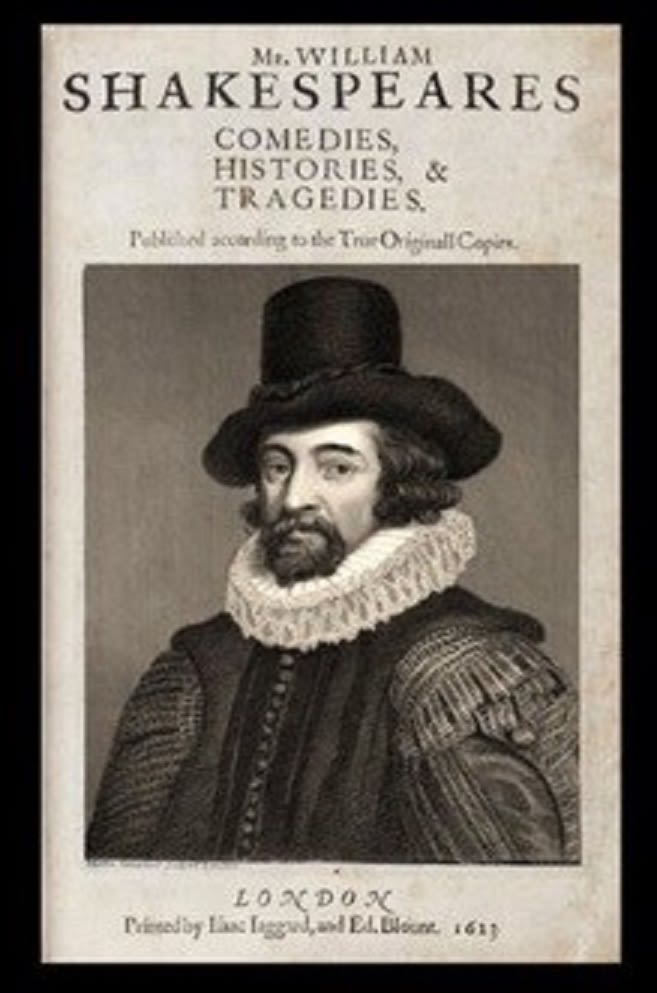

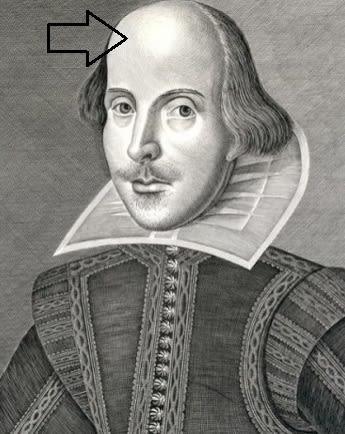

In fact, no one appears to even know for sure what Shakespeare looked like. The images you see here are all guesswork and artistic license.

Some people might say, "They are great plays and sonnets, why does it matter who wrote them?"

The answer lies in the pursuit of truth, and ensuring the accuracy of historical claims. It is about maintaining academic rigour and integrity in the study of literature and history. There is an evident double standard when some academics insist on empirical evidence in scientific experiments, while simultaneously perpetuating an unsupported assertion about Shakespeare. It highlights hypocrisy in their approach.

Even Shakespeare's birthdate may not be accurate. The entry for his baptism is 26th April, 1564. The 23rd is used as his birthday because baptisms were traditionally held three days after one's birth in that era.

Although this baptism does appear in the parish register of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon, the original document is no longer extant. Instead, later copies and transcriptions of the entry have been used by historians to study Shakespeare's early life.

Due to the lack of the original document it is, therefore, possible to argue that the entry may have been inserted or altered. This carries weight because on Shakespeare's Stratford memorial it states he was 53 when he died, yet if born in 1564 he would have been turning 52 in 1616.

The inconsistency between the age on the monument and the calculated age at the time of his death has been a subject of debate and speculation among scholars and interested parties for centuries; not least because the orthodox narrative holds that Shakespeare died on the same date he was born.

This date, 23 April, rather conveniently, just happens to be the day that England celebrates its patron saint, St George. Furthermore, St. George is often depicted in iconography or artwork brandishing a spear.

Be under no doubt, there are many other reasons to be very cautious about accepting the unswerving belief of the Establishment that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare. I say this, not to sound anti-establishment, but only because it is common sense.

Hard data is difficult to find about the entire industry, but reasonable estimates would put the total revenues derived from global Shakespeare-related tourism, performances, film/TV, merchandising, education, publishing, etc., as likely to be around 400 million pounds - nearly 500 million USD - annually, possibly far greater. It stands to reason that many of those people, industries or countries who profit from the industry might have a vested interest in 'selective emphasis' to present a picture that more closely fits a preferred narrative.

A person who believes that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare is known as a Stratfordian. While some Stratfordians will have no vested interest, and genuinely believe the man from Stratford wrote the plays, it would be more intellectually honest for everyone to acknowledge that there is no definitive or conclusive evidence that proves Shakespeare wrote the works attributed to him , and there are some factors that cannot be easily explained.

What are these 'factors'? Well, aside from the ones already mentioned, take a good look at this famous image.

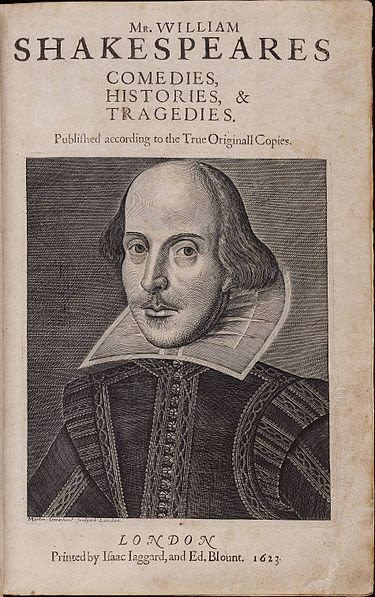

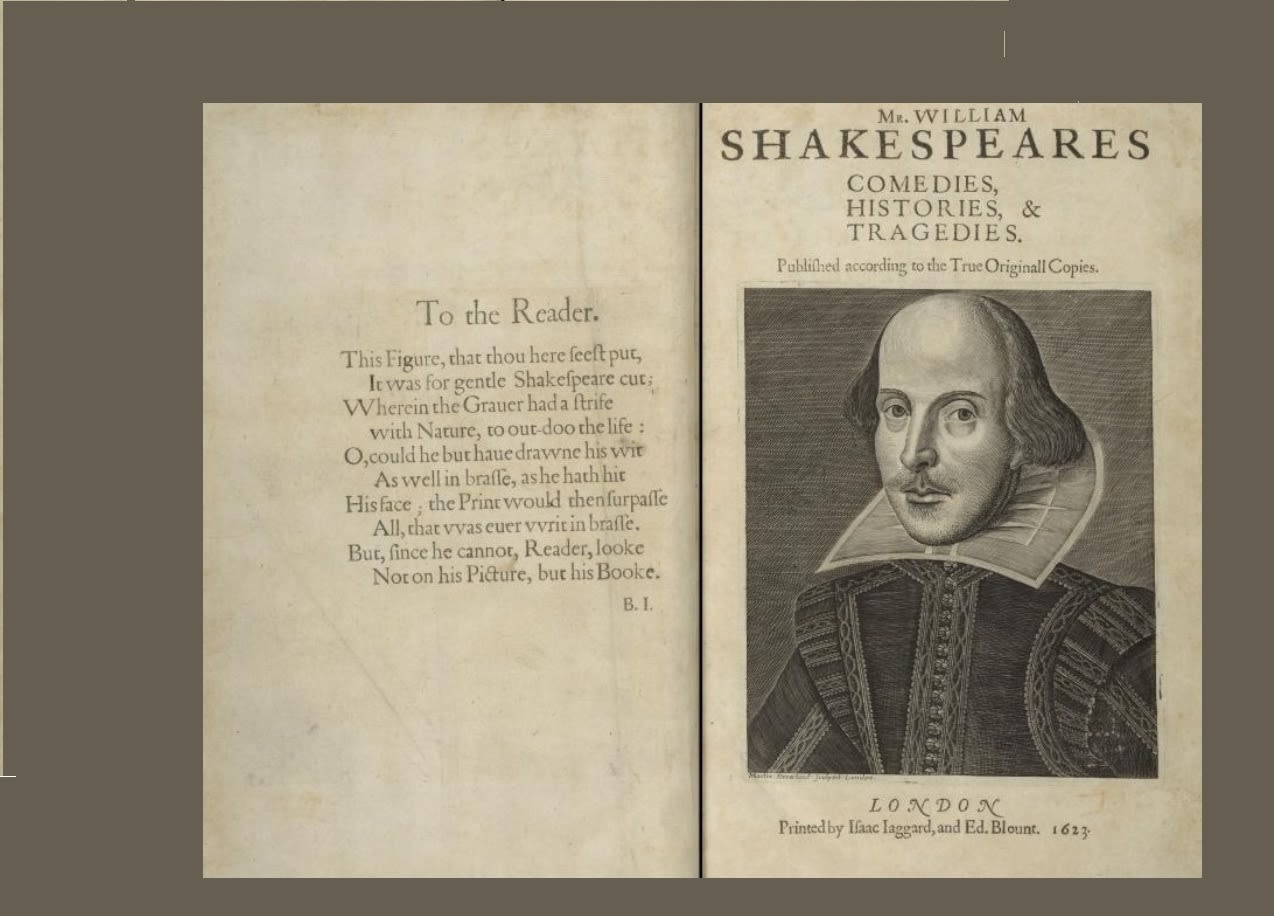

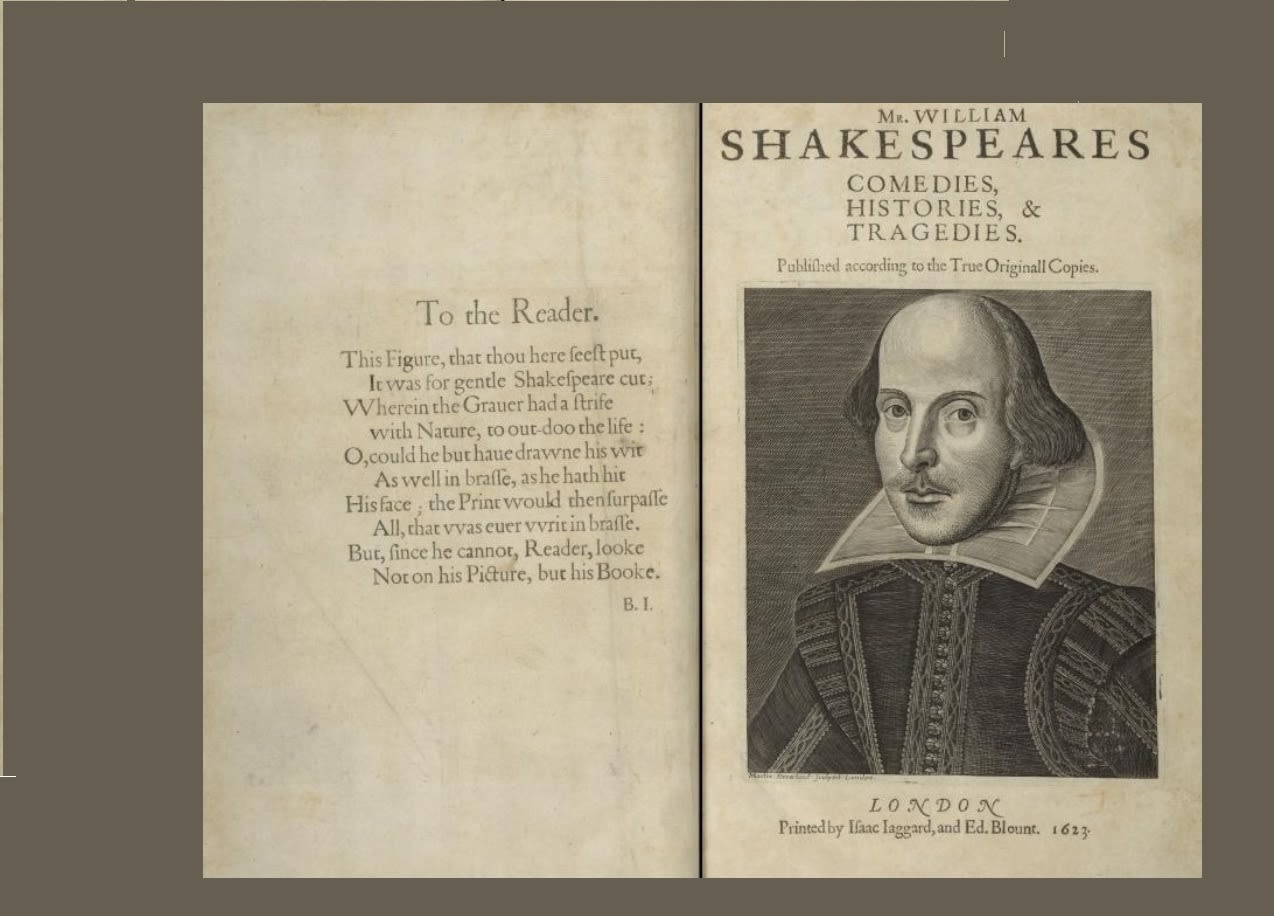

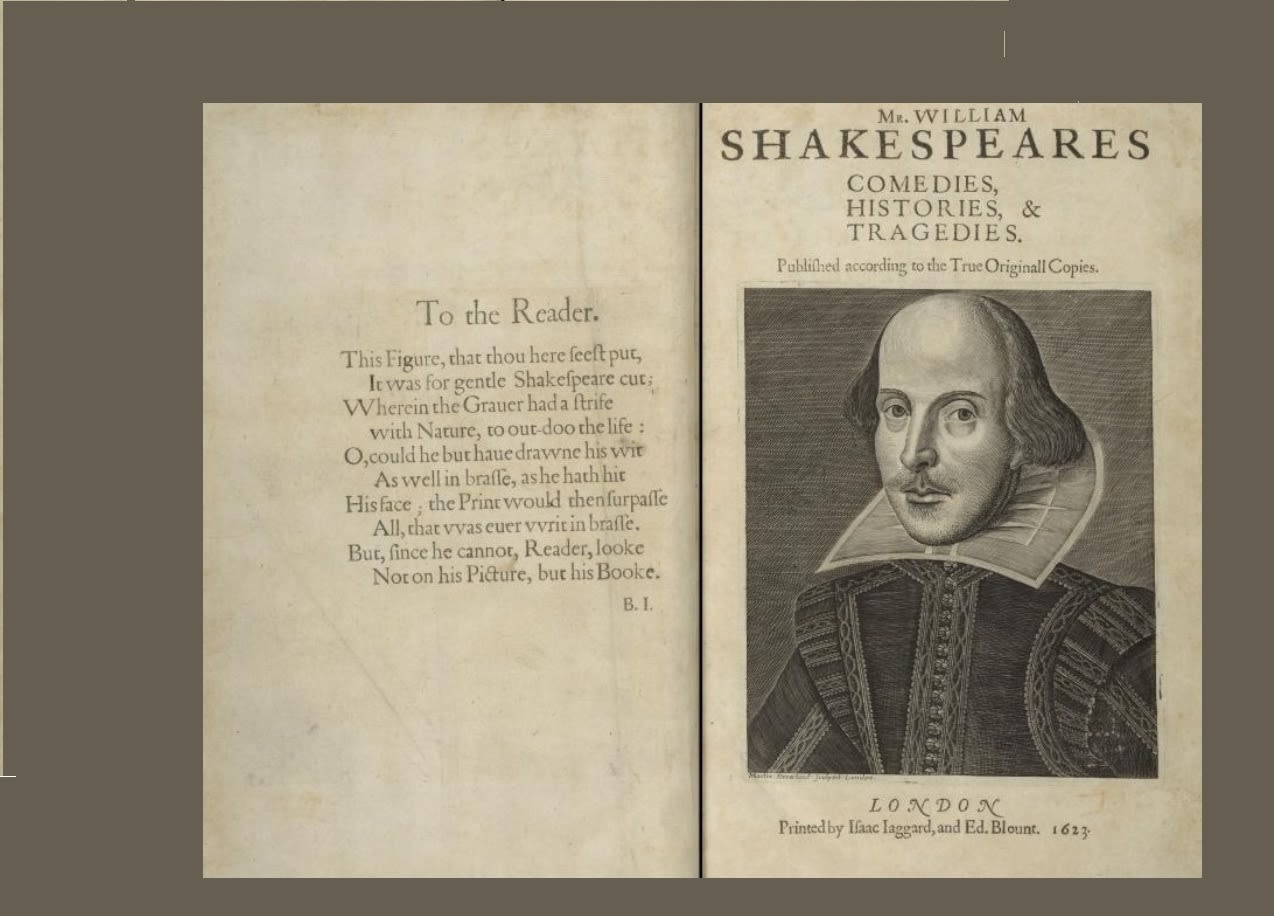

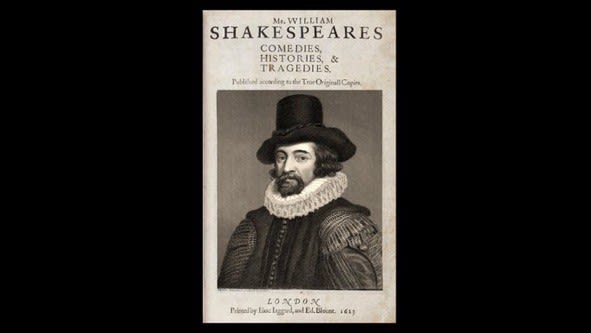

The engraving is known as the Droeshout Portrait. It graces the title page of the first collected works of Shakespeare, commonly referred to as the First Folio. It was printed in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare's death.

If you look closely at the image you can see an unnecessary line drawn from the right ear to the chin. This gives the appearance of a mask.

The head being unnaturally high off the body, the expressionless face, and the tailoring anomalies have also been endlessly debated. As has the circular Sun-like illumination on his oversize forehead .

There is also the small matter of the Sun's rays that emanate from below the chin onto the unusual spade-shaped ruff .

This style of ruff, called a standing collar, appears very infrequently, and then only in images of those from the nobility, and usually covered in lace - not Sun rays. The closest similarity to this exact ruff that anyone appears to have found is one worn by German military warriors.

Some of these oddities have been explained away by Stratfordians as being the result of the inexperience of the engraver, Martin Droeshout. It is thought that he had yet to adequately master the art of perspective. Also, as Shakespeare was no longer alive, it is likely Droeshout was having to rely on paintings, possibly the Cobbe or Chandos portrait, to capture his likeness and attire.

However, neither of those paintings have been conclusively proven to be depictions of Shakespeare.

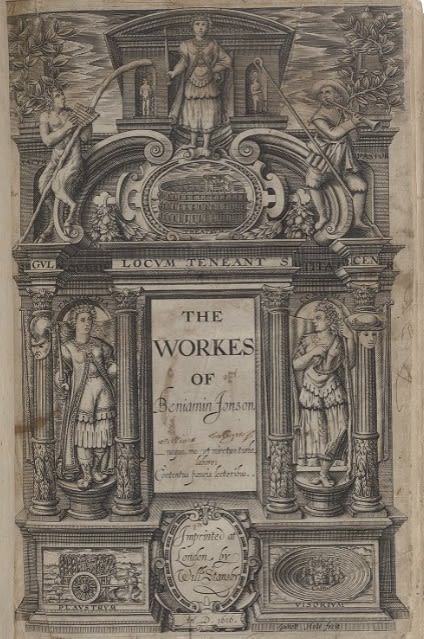

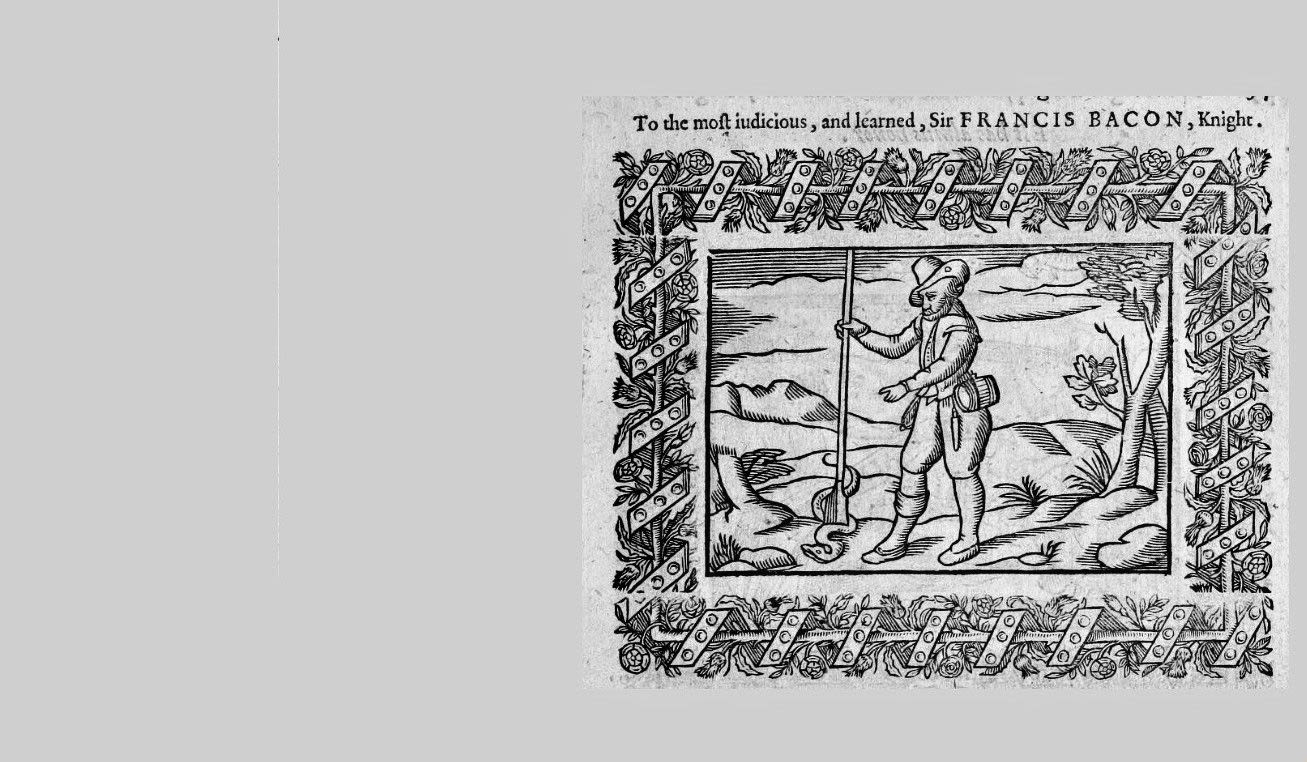

Given that we know a great deal of time and money would have gone into the production of the First Folio, and this was the first time that a large picture of a person had been used as a title page - normally it would be an architectural image like the one below - it raises further questions.

A common type of frontispiece

A common type of frontispiece

Namely: Why would an inexperienced engraver who would only have been 15 years old when Shakespeare died, have been chosen for such an epic, new and expensive project?

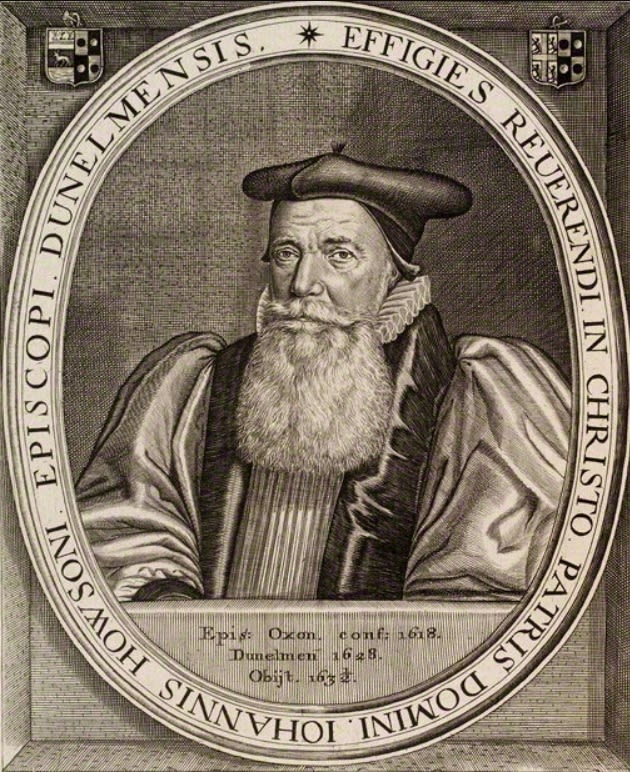

Additionally, why was the portrait of this man so devoid of any adornment, such as heraldry or motto? Here is one of Martin Droeshout's later engravings where these were present.

Rev. John Howson by Martin Droeshout

Rev. John Howson by Martin Droeshout

It is true to say, Droeshout's engraving in the First (Shakespeare) Folio has been mercilessly lambasted and lampooned for centuries.

One portrait painter (Boaden) described it as 'an abominable libel upon humanity.' Another called it 'vulgar art'.

You can read more caustic observations in a full paper at Academia. edu about the Droeshout Portrait here.

There are many other factors that give rise to suspicions regarding the authorship of the plays and, likewise, the Shakespeare sonnets. Not least that Shakespeare only had a grammar school education, he never left the country and his children and wife were illiterate. Given William Shakespeare's reputation as a brilliant writer, it seems reasonable to assume he would have taught his family some rudimentary writing skills during his lifetime. However, this appears not to have been the case.

I cannot cover all the anomalies in this article, but I will just mention in more detail ...

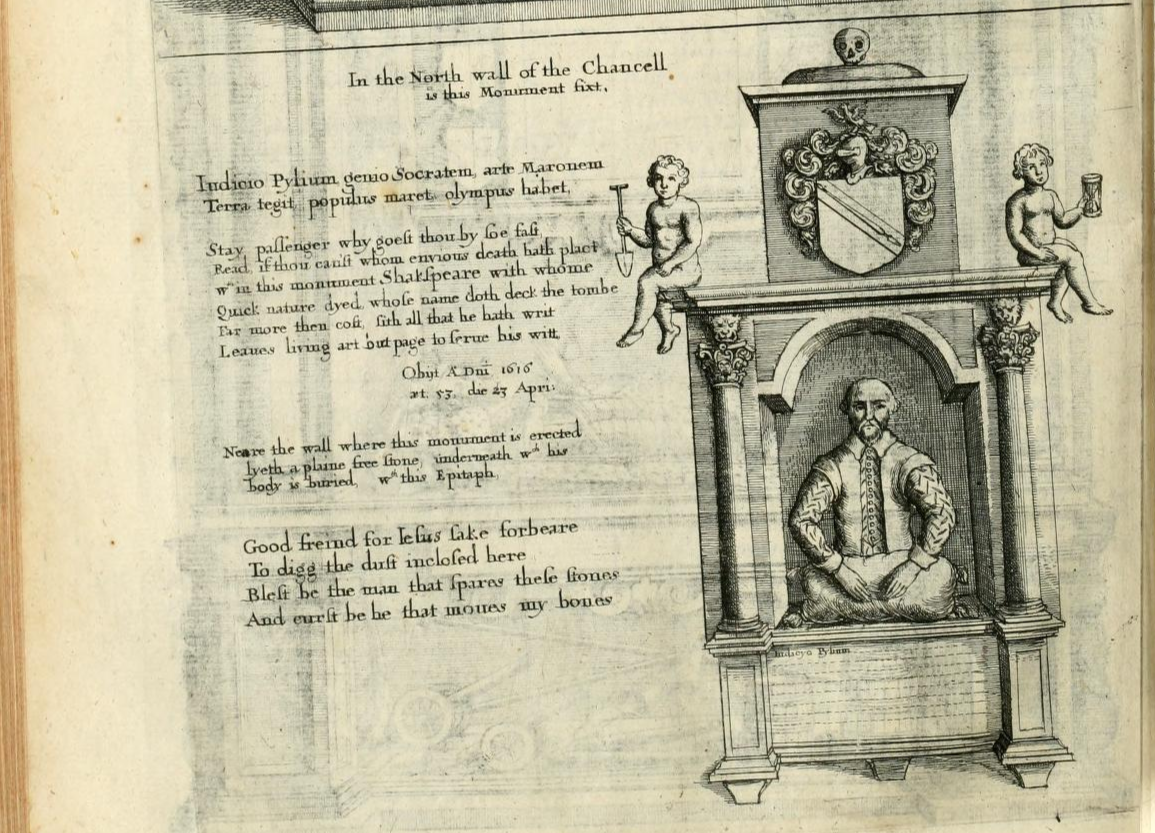

The Funerary Monument

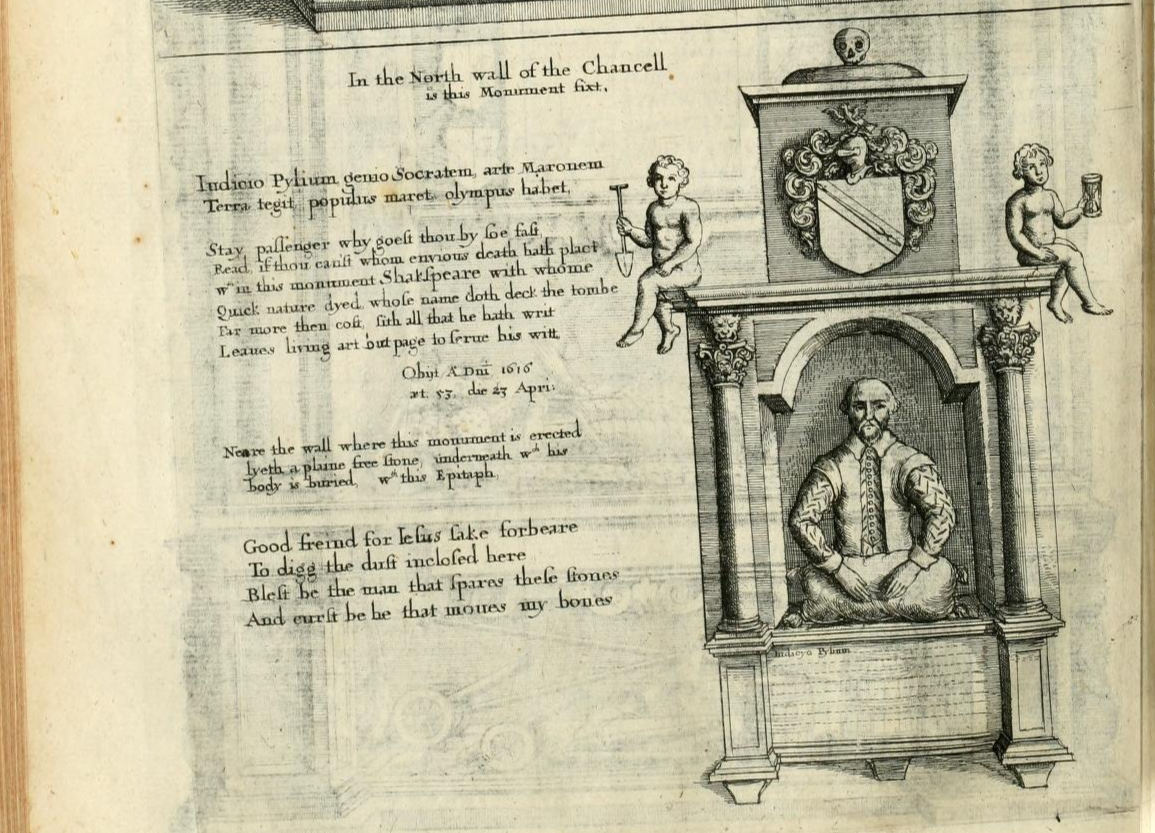

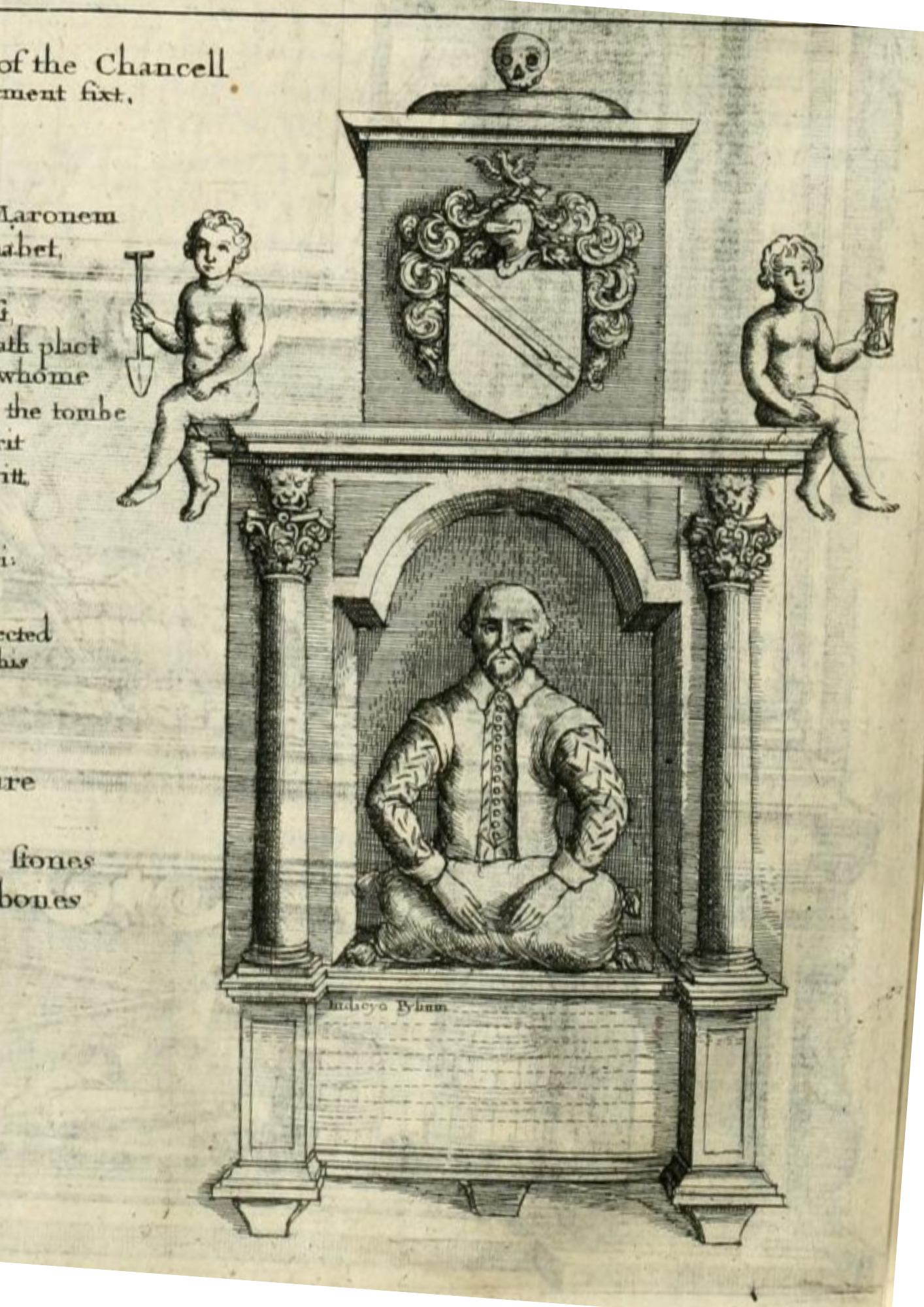

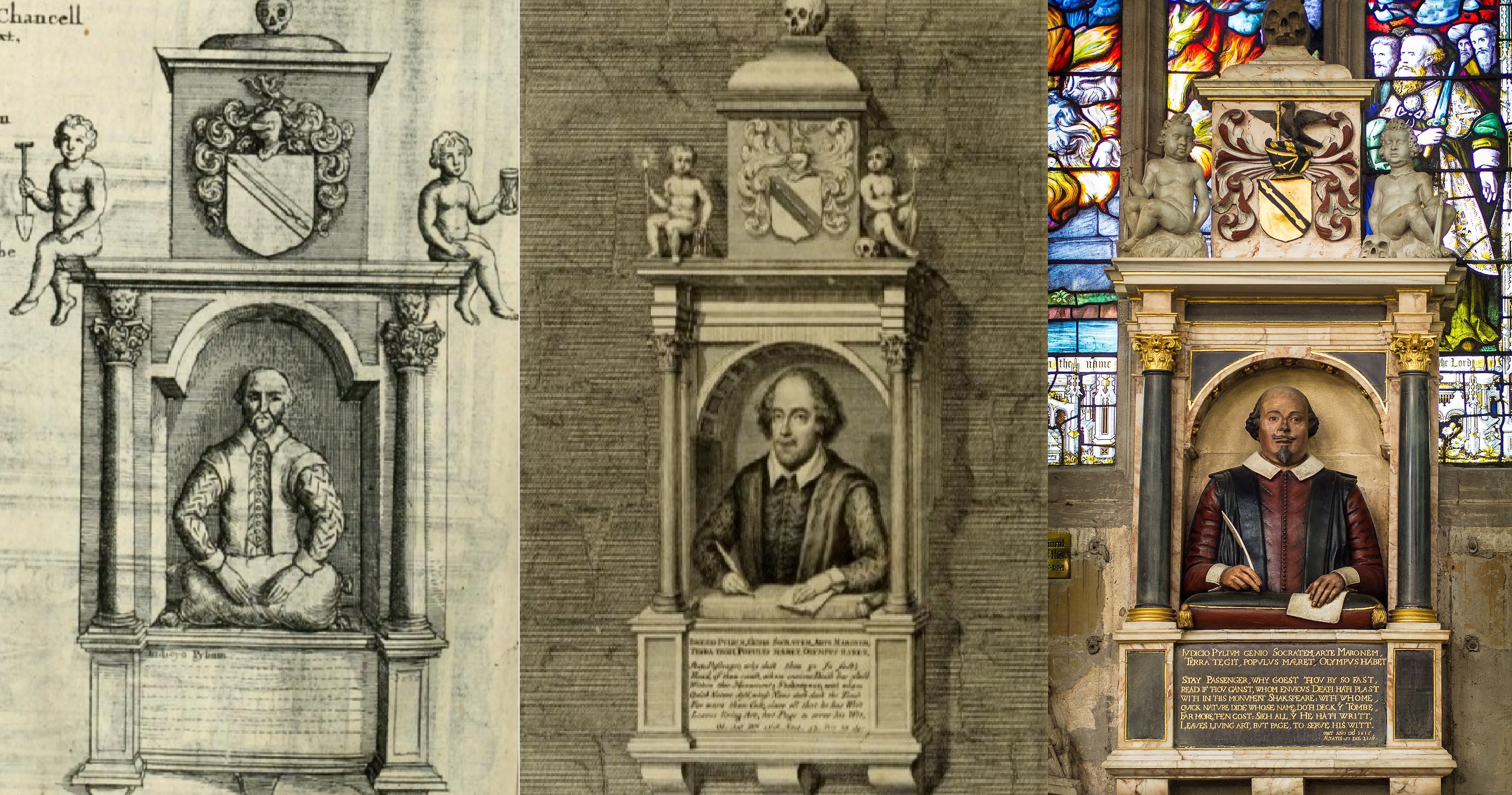

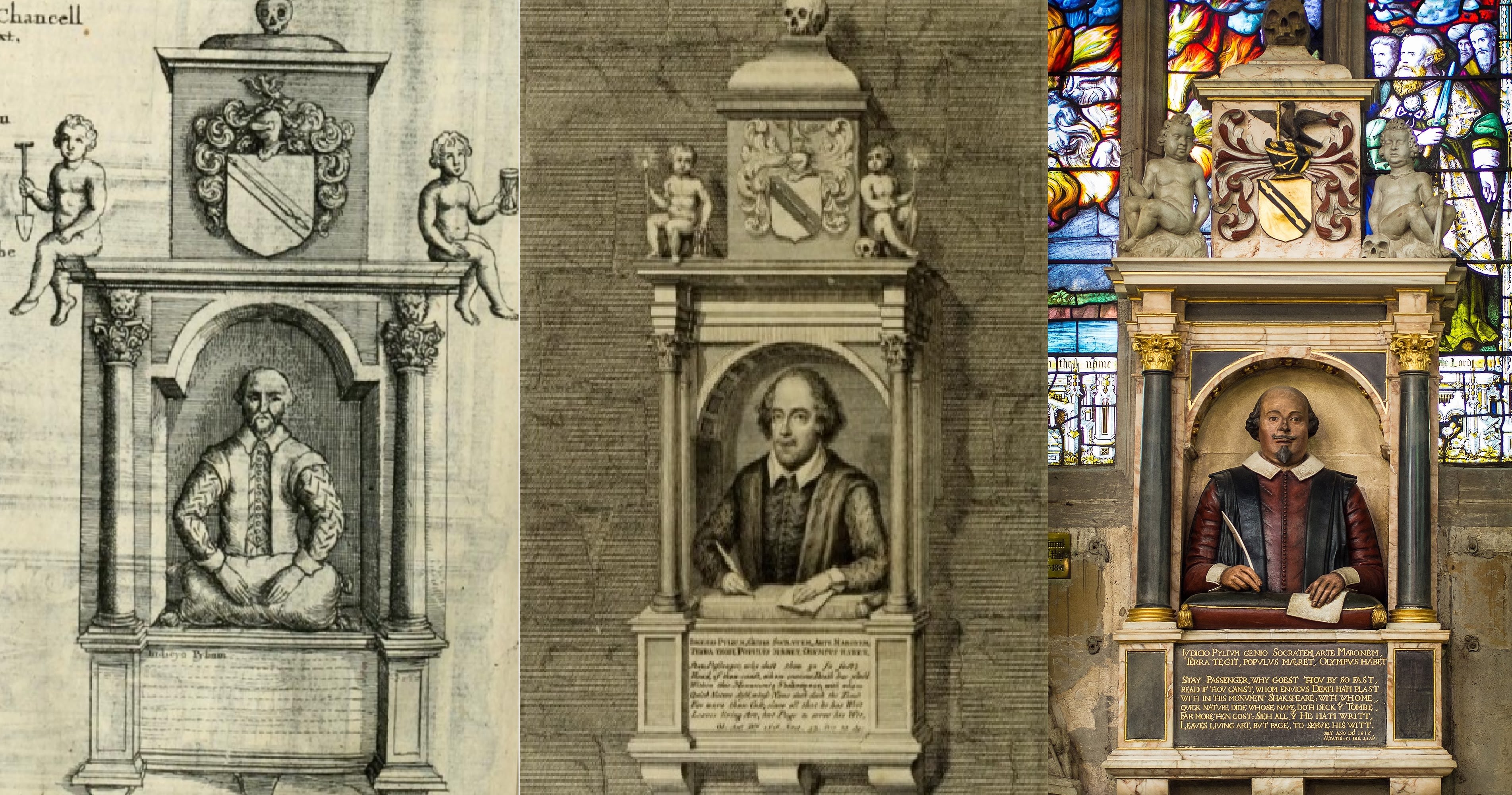

The next image is the first-ever printed image of the funerary monument. It was erected in honour of Shakespeare and located on the North wall in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford -upon-Avon, Warwickshire.

This monument is believed to have been erected sometime after Shakespeare's death in 1616, but prior to the printing of the First Folio in 1623. Mysteriously, however, no documents concerning its original commissioning or installation have survived.

All we know is that the monument was sketched from sight by Sir William Dugdale in 1634. The sketch was then engraved by the highly revered, Wenceslaus Hollar and the engraving was included in Sir William's book, Antiquities of Warwickshire in 1656 (above and right).

Sometime after 1656 the original monument in Holy Trinity Church was modified and the bust was replaced with a new one. This more closely resembled the Droeshout engraving.

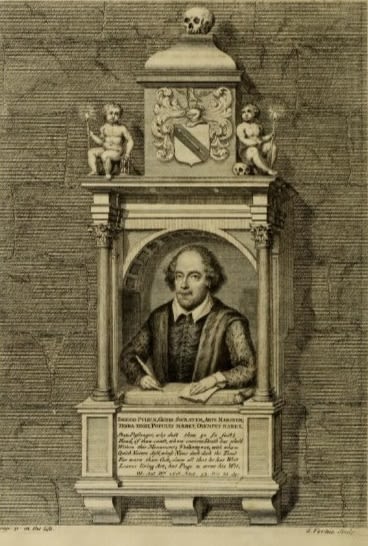

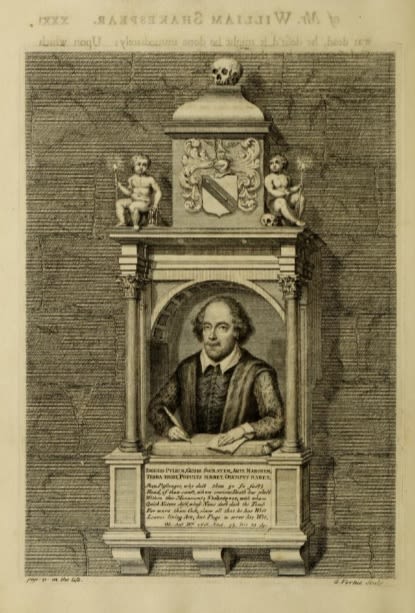

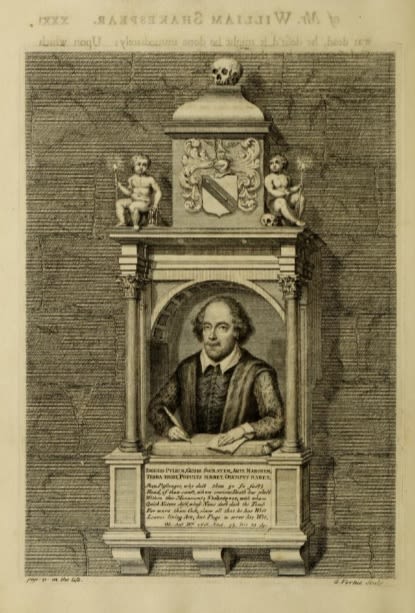

Here you can see an engraving by George Vertue, showing this later monument. It appeared in Alexander Pope's 1725 edition of The Works of Shakespeare.

Compare it to the Droeshout portrait.

It's a much better likeness, but very different to what Sir William Dugdale saw.

Dugdale's rendition

Dugdale's rendition

The face in the later memorial bust has become slightly broader and more youthful looking than in Sir William's rendition, and a quill and piece of paper have been added. The woolsack, which was very prominent in the original, has also changed to become a flat cushion upon which paper now rests. More differences are readily apparent, both in architectural and other detail.

Between 1746 and 1748 another major beautification and restoration project was undertaken on this monument. In fact it is documented that the entire bust was removed and a plaster cast taken. The monument then morphed into one which now looked like a very broad-faced, if not slightly podgy man, with a short stubby nose and unusual beard.

In 1798 the entire monument was painted over in white. It was then re-painted in colour and repaired again.

The wide faced man, who bears little resemblance to the Droeshout portrait, and none whatsoever to Dugdale's, from-sight depiction, is the one that remains in situ to this day.

Is any of this taught in school? Are visitors made aware of this unusual history?

Here are three versions of the monument side by side

Note the introduction of quill and paper

Francis Bacon was Imperator of the Rosicrucians

Francis Bacon was Imperator of the Rosicrucians

Unravelling the Mystery:

So what was going on?

Well, setting out the motivations behind the possible cover-up of the true authorship of the works of Shakespeare requires that we unravel a complex tapestry of intrigue. We also need to try and put ourselves in the shoes of those who lived through a tumultuous religious and political period in English and European history.

The Hidden Hand of Sir Francis Bacon:

Proponents of the Baconian theory, of which I am one, are called Baconians. Most Baconians believe that Francis Bacon, renowned philosopher, scientist, and statesman of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, along with his intellectual circle, known as his 'Good Pens', orchestrated an elaborate scheme. One which would attribute the works of Shakespeare to a frontman while preserving their own anonymity.

But why would they have engaged in such an audacious deception? Let's take a look at a few possible reasons:

Political Subterfuge:

Bacon, a man deeply embedded in the political landscape of his time, had ambitions that extended beyond his scholarly pursuits. Using the actor Will Shakespeare as a front would have allowed him to express political and controversial ideas without directly associating himself with them. This would have enabled him to navigate the dangerous political climate and avoid potential repercussions, while still disseminating his moral and ethical philosophies.

It is important to appreciate that during the period in which Bacon lived (1561-1626), heresy was considered a serious offence, and religious conformity was strongly enforced.

Secrecy and Clandestine Networks:

It is believed that this group of people, headed up by Bacon, sought to challenge the established order and advance knowledge. By attributing the works to a fictitious figure like Shakespeare, they could operate discreetly, shielded from the prying eyes of authorities and conservative forces that sought to stifle intellectual freedom. This subversive approach would have ensured the preservation of their ideas and safeguarded the collective pursuit of spreading knowledge (illumination).

Immortality Through Artistic Legacy:

Bacon and his intellectual circle recognised the power of literature and its ability to transcend time. By attributing the works to Shakespeare, they were likely seeking to create an enduring legacy that would immortalise their ideas. Through this grand deception, Bacon could leave a lasting impact on the world, ensuring his ideas would be viewed by the illiterate in the form of plays, and read by the literate. In this way the key moral and ethical insights would be absorbed, remembered and celebrated in many lands for generations to come.

To maintain the façade, and protect their freedom and lives, Bacon and his cohorts would have needed to ensure that their involvement remained hidden, or 'veiled', using pseudonyms, intermediaries, and layers of obfuscation. The suppression of their true identities, coupled with the use of codes and cipher (a popular method of communication at the time) and lack of explicit documentation, has contributed to the enduring mystery surrounding Shakespeare's authorship.

It was an intricate web of secrecy woven by Bacon and his fellows - members of his Invisible College and sometimes referred to as the 'Invisibles'.

The full name of Bacon's Invisible College was The Rosicrucian College of the Six Days Work. Their symbol was the Rose, and the term Rosicrucian stems from the amalgamation of the Greek word Rhodo, meaning Rose, and the Cross, (Rosy Cross) hence the link to Shakespeare's birth and death on St George's Day as St George wore a red cross, as well as brandishing a spear.

It is also known that Pallas Athena, the Goddess of Wisdom, was a muse of Bacon's. In myth, she wore a helmet of invisibility and carried a spear (of light) . Athena, whose name starts and ends in AA (a known cipher of the College which was emblematically concealed in the headpieces in the First Folio), was a spear shaker. So, as you can discern, there is a double cryptic link in the Knight, Francis Bacon, utilising the name of the actor William Shake-Speare to mask the true authorship of the plays. Especially because in Rosicrucian texts, SS or Sancti Spiritus is described as the source of divine inspiration, wisdom, and truth that illuminates the mind.

The term Rosicrucian first became widely known from the three enigmatic and influential 'manifesto' texts. The first of which was called the "Fama Fraternitatis Rosae Crucis" (The Fame of the Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross), published in 1614 in Germany.

Francis Bacon was Imperator of the Rosicrucian College. The Imperator was known as a Father or Master (1) and usually has 12 main 'disciples', 13 in total. The men (and it is thought, some women too) who he involved were not known as disciples but as Fellows or Sons - hence why you may also hear of them being referred to as Sons of Light. Due to working in secrecy they were also sometimes referred to as Knights of the Helmet, a nod to a) Pallas Athena and her helmet of invisibility b) to Knights and c) to the secrecy that the wordplay of Knight (Night) conveys.

It should be made clear that the Rosicrucian movement was neither a cult nor a religion, but was comprised of a diverse range of fellows, including intellectuals, natural philosophers (precursors to scientists), nobles and aristocrats. They worked for the betterment of humankind, helping to build a New 'Atlantis' - a new Jerusalem, a land - and indeed a wider world - of illumination, based on moral, ethical and other broader spiritual and philosophical ideals, free from religious dogma.

The collection of Shakespeare plays were the covert vehicle by which Bacon knew each person, regardless of their status, could come to understand more about the weaknesses and strengths of human nature. The plays touch upon love, ambition, power, fate, justice, loyalty, betrayal, and many other fundamental aspects of human existence. They provided a treasure-house of insight, wisdom and knowledge that could subtly lead to spiritual and personal transformation, and an understanding of the human condition.

Meanwhile his many overt, publicly-lauded works written under his own name, sought to uncover truths about the nature of God's works, the universe and humanity's place within it. Bacon helped set a new standard in the method of discovery, through reason and empiricism, that we know today as the Scientific Method.

In his hidden capacity then, Bacon and his pens were disseminating information utilising allegory, allusion, metaphor, and other symbolic language, to convey deeper meaning about universal principles, ethics and morality that transcend the dogma and doctrine of any one religion.

In ancient times, many philosophical and mystical belief systems developed foundational wisdom by observing and venerating the natural world. Thinkers and sages studied the cosmos, natural patterns and forces to shape early insights about existence. These wisdom keepers perceived the intrinsic unity underlying all existence.

Though experienced as dualities - light and dark, life and death, heaven and earth - these were seen as two sides of one coin; microcosms reflecting macrocosms. The ancients discerned an indivisible whole, amidst the multiplicity.

This generally went against the predominant theological teachings of the Christian Church, especially during the Renaissance period in Europe when mystics like Giordano Bruno, who promoted cosmic unities, were persecuted as heretics.

Bacon and his Rosicrucian 'Good Pens' could get around this heterodoxy - censorship - by presenting views in plays using the cover of Shakespeare. Indeed, the exploration of the thematic motifs of duality are prevalent throughout the works of Shakespeare.

Here are five examples of how the works educate us all, allowing us to discover new layers of meaning and contemplate the profound themes embedded within the plays, generation after generation:

1. Light/Dark Imagery:

The Rosicrucian/Shakespeare plays frequently employ imagery of light and dark, mirroring the concept of duality and the interplay between opposing forces. In "Romeo and Juliet," for instance, the famous balcony scene juxtaposes light (representing love and hope) with dark (symbolising secrecy and danger). This recurring theme underscores the idea that life encompasses both positive and negative aspects, and that understanding and reconciling these dualities is an essential part of our existence.

2. Macrocosm/Microcosm and Universal Themes:

Many of the plays explore universal themes that reflect the interconnection between the larger world and the individual. The idea of "as above, so below" is evident in characters who embody universal traits or archetypes, such as the ambitious Macbeth grappling with his conscience or the complex Hamlet, contemplating the nature of existence and life and death.

3. Cryptic Clues and Acrostics:

The Rosicrucian 'Shakespearean' works contain numerous instances of wordplay, hidden messages, and puzzles, alluding to duality. The "To the Reader" letter in the First Folio contains subtle clues and acrostics that hint at deeper meanings. While the interpretation of such clues is subjective, Bacon and his Good Pens would have known that, one day, the presence of cryptography would invite further exploration and analysis of the works.

4. Theatrical Ambiguity and Open-endedness: The Rosicrucian/Shakespeare plays often exhibit a deliberate ambiguity and leave room for multiple interpretations. This openness allows individuals to project their own perspectives onto the texts and engage in intellectual discourse, fostering a sense of individual exploration and freedom of thought.

5. Love and Liberation:

The plays often delve into the transformative power of love. Characters like Romeo and Juliet, who defy familial feuds for the sake of love, or Beatrice and Benedick, who break through their witty banter to discover a deep connection, exemplify the liberating force of love that transcends societal boundaries and expectations.

Freedom of thought and education of the masses was the overriding aim because, as Bacon famously said: Knowledge is power. The creative linguistics of the works of Bacon/Shakespeare are also responsible for introducing (and popularising) around 1,700 new words and phrases into the English language.

Lamp of Tradition

In authoring the works of Shakespeare, Bacon was carrying the "Lamp of Tradition" over from the generations before him.

Mystic Christianity, Renaissance Humanism and Hermeticism provided a general ideological backdrop that informed Bacon's perspective, and these encompassed various different ancient influences from Europe and the near and far East. In the Bhagavad Gita, a series of texts written in the 1st century BC. Chapter 5. Verse 16 says:

"In those who have banished ignorance by Self-knowledge, their wisdom, like the illuminating sun, makes manifest the Supreme Self”

Commentary on this passage says: In the darkness of ignorance, we identify ourselves with the body, and consider ourselves to be the doers and enjoyers of our actions. When the light of God’s knowledge begins shining brightly, the illusion beats a hasty retreat, and the soul wakes up to its true spiritual identity.

The Rosicrucian teachings are about recognising this identity and the unity of the Cosmos. Man is a soul temporarily having a human experience, but always interconnected with an omniscient, universal mind - God.

Now we can perhaps all better understand why the light shining like a Sun from the forehead, or the Sun's rays emanating from underneath the 'mask' of the face in the Droeshout Portrait, would have been details that were deliberately included. It all cryptically signalled that an illuminated soul (Bacon) lay beneath the mask - a soul who was here to teach and advance humanity.

In Conclusion

Although at the time of publication of the First Folio, only the nobility and wealthy merchants could afford to purchase a copy, Sir Francis Bacon and his group of 'Invisibles' knew that by putting an actor called William Shakespeare forward as their 'author mask' they could reach a huge audience.

They knew that the plays would have a form of immortality, carrying their secular insights forward for generations to come, and thus fulfilling the mission of their Rosicrucian Brotherhood as a reformist movement dedicated to the universal transformation of society, through spiritual and intellectual means. 'Shakespeare' imparts an understanding of our commonality (common-wealth, in the form of the value of the light of knowledge) for the common good.

The Shakespeare authorship question and its connection to the Rosicrucian movement has been a tantalising enigma, but it was known that one day in the future, times would not be so restrictive and truth about the authorship would surface. Hence why one of the Rosicrucian texts said: The entire march of time reveals what is hidden and on the front of Bacon's New Atlantis are the words in Latin, Tempore patet occulta veritas: Time reveals hidden truth.

I invite everyone reading to question the history and narratives we have come to accept without deeper scrutiny. The Shakespeare Authorship Question should, from now on, perhaps not focus so much on who wrote the works - we can be sure that a key document proving the author to be Bacon will surface at exactly the right time - but on a contemplation of what, in the four hundred years since the printing of the First Folio, have we managed to learn from them, and move forward with.

For example, Shakespeare's characters are profoundly complex and multi-dimensional, showing how virtues and flaws can exist in the same persons. Where are we still striving to embrace the full spectrum of humanity or the futility of war and violence?

Shakespeare conveyed anti-war messages in many plays. Yet armed conflict persists. The works compel us to continue seeking non-violent means of resolving conflicts. Are we doing that?

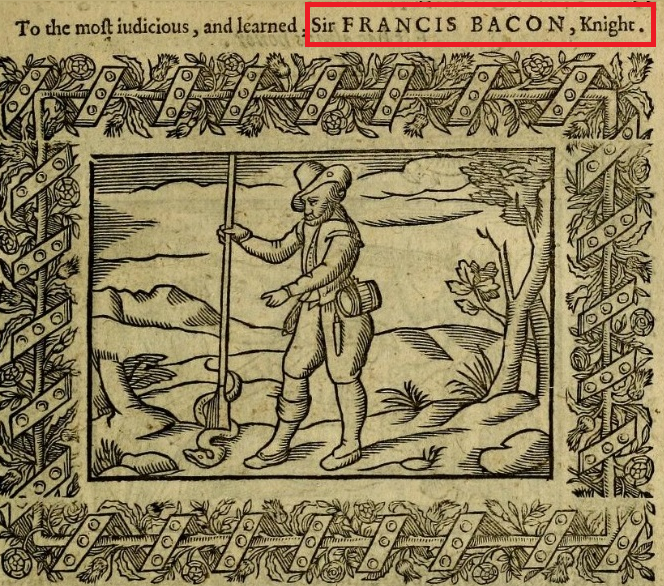

I'll leave you with this emblem.

It was dedicated to Sir Francis Bacon in the 1612 book, Minerva Britanna (Minerva is the Roman counterpart to his muse, the Greek goddess, Pallas Athena). Here a man in a Baconian hat, uses a spear (which depicts both light and dark shading on its spade-shaped end) to slay the serpent of ignorance, just like St George slays the dragon.

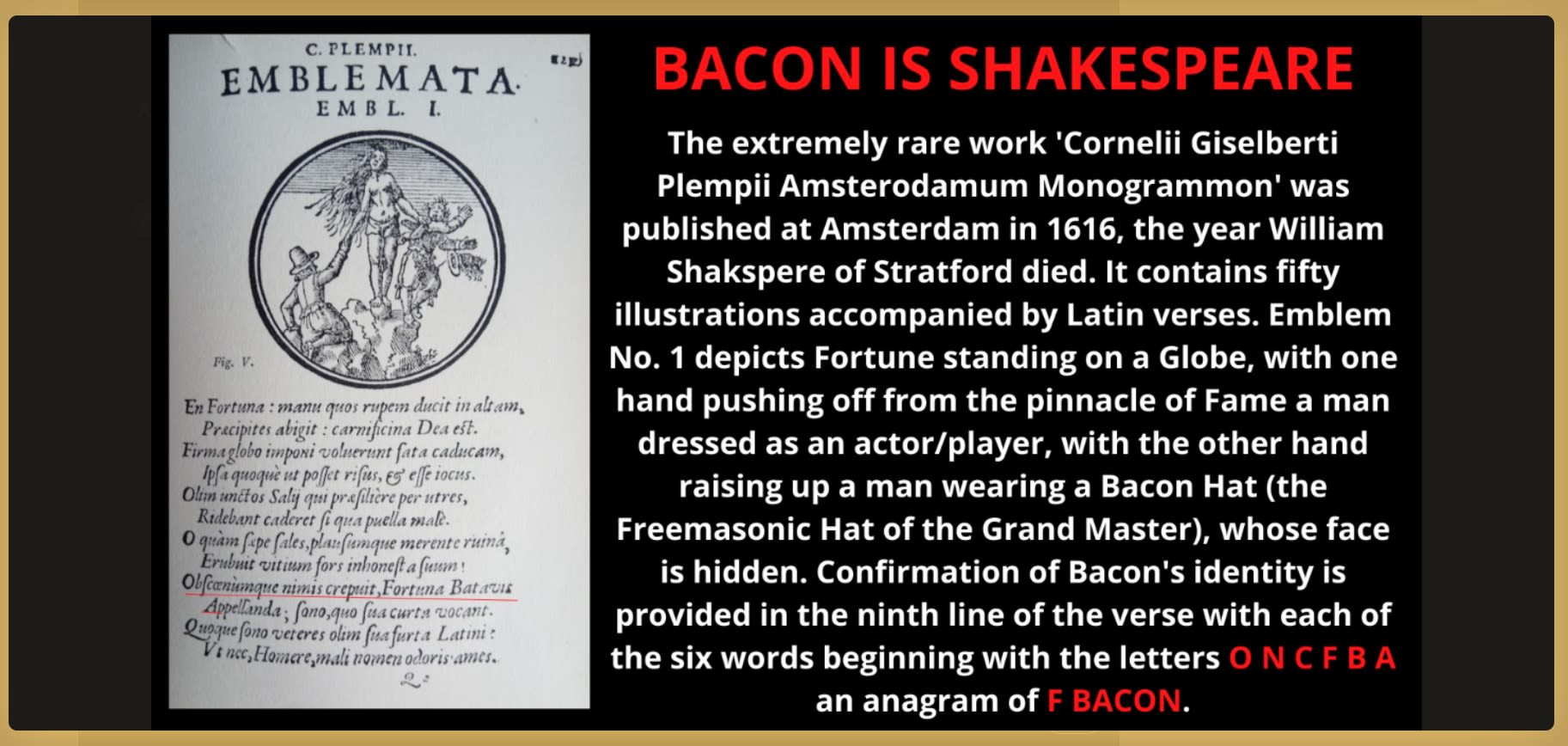

Another emblem emerged in 1616 (see below) the very year Shakespeare died on St George's Day. It shows a man in the same Bacon hat, whose face is hidden, being raised up by Fortuna (who represents the wheel of life or fortune) while a man dressed as an actor/player falls off the pinnacle.

Twitter @Baconspeare

Twitter @Baconspeare

The deeper meaning of this is that, as the world (the wheel of fortune) turns, the natural order of everything is dual and life perpetually cycles between two states: rise and fall, hidden to revealed, darkness to light, ignorance to wisdom, age to age, etc., and back round again. It is never-ending and the only way to navigate our path is to recognise this pattern of Nature and find balance. Bacon's family motto was Mediocria Firma: The Middle Way is Best.

Similar to understanding emblems, once everyone knows to look at, and/or listen to, the collected works of 'Shakespeare' (the Comedies, Histories, Tragedies and Sonnets of love) with the right eyes and ears, seeking out the timeless, ancient wisdom they contain, we can accelerate personal growth.

As Grand Masters, like Sir Francis Bacon, have always known, everywhere we look we find others reflecting ourselves in the exquisite light of understanding. We are not isolated individuals, but rather fellows in this human experience, and we need to embrace our shared humanity and our connection to All that is.

Please keep scrolling.

Thank you for reading.

If you would like to know more about Francis Bacon and the Shakespeare authorship question, please visit SirBacon.org

Meanwhile, my non-fiction book The Secret Work of an Age: Piercing the Veil by K. J. Cassidy was just released on Amazon in paperback form. It covers information about Bacon in the first chapters, and the rest is packed full of information and secrets, largely only known to initiates of the Mystery schools. It has been recommended by Rosicrucians and Freemasons for others (including other Freemasons) to read, as it covers the more esoteric side of the Craft. Visit Amazon or The-Secret-Work.com

Kate

Editorial Review from Dr David Harrison. A Masonic historian and leading academic expert on the study of Freemasonry.

The Secret Work of an Age is a book that produces a worthy compendium of esoteric signs, symbols, gematria and hidden meanings, discussing the Cabala, Rosicrucianism, Gnosticism and of course, Freemasonry, which acts as a gateway to other Orders, creating a pathway for esoteric research. Indeed, this book certainly produces an excellent guide for the journey.

The work delves deeper into the esoteric nature of Freemasonry than most other books that I've recently read. The reader will find a converging amount of esoterica, from numerology to ancient mythology, all colliding to create a thoughtful account of the mysteries that lie underneath the surface of of Freemasonry.

From the measurements and dimensions of ancient structures, to geometrical symbols, this book will guide you through a wealth of knowledge, and it should be a must for anyone wishing to know the deeper esoteric meaning behind Freemasonry and its adjacent Orders.

www.dr-david-harrison.com